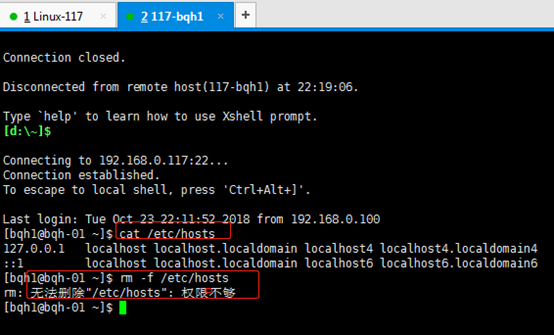

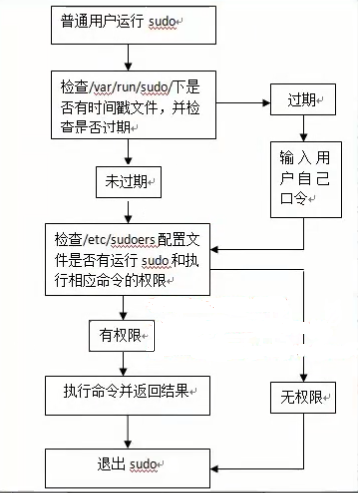

The logs can facilitate a problem-related postmortem to determine when users need more training. Using the sudo command does have the side effect of generating log entries of commands used by non-root users, along with their IDs. Users who need to continue working with elevated privileges but are not ready to issue another task-related command can run the sudo -v command to revalidate the credentials and extend the time for another 5 minutes. During this brief time interval, usually configured to be 5 minutes, the user may perform any necessary administrative tasks that require elevated privileges. In most cases, sudo lets a user issue one or two commands then allows the privilege escalation to expire.

SU VS SUDO FULL

The sudo command does not switch the user account to become root most non-root users should never have full root access. The sudo command gives non-root users temporary access to the elevated privileges needed to perform tasks such as adding and deleting users, deleting files that belong to other users, installing new software, and generally any task required to administer a modern Linux host.Īllowing the users access to a frequently used command or two that requires elevated privileges saves the sysadmin a lot of requests from users and eliminates the wait time. The original intent of sudo was to enable the root user to delegate to one or two non-root users access to one or two specific privileged commands they need regularly.

This difference is due to the distinct use cases for which they were originally intended. These tools both provide escalated privileges, but the way they do so is significantly different.

Most sysadmins rarely use sudo because it requires typing more than necessary to run essential commands. Some days require staying logged in as root all day long. Many sysadmins log in as root to work as root and log out of our root sessions when finished. A user might need to run one or two commands as root, but very infrequently. There were usually many non-root user accounts on those computers, and none of those users needed total root access. The root user would also have a non-root account for non-root activities such as writing documents and managing their personal email.

SU VS SUDO PASSWORD

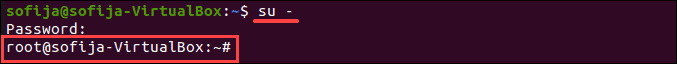

In this ancient world, the person entrusted with the root password would log in as root on a teletype machine or CRT terminal such as the DEC VT100, then perform the administrative tasks necessary to manage the Unix computer. Early Unix computers required full-time system administrators, and they used the root account as their only administrative account. The su and sudo commands were designed for a different world. If you run the following commands: $ sudo -sįrom this, you can see that sudo -s does not simulate an initial login, and does not change $HOME.Our latest Linux articles Historical perspective of sysadmins Meanwhile, sudo -s starts a new shell but without simulating initial login - login files are not read and $HOME is still set to your user's home folder. This also means sudo -i reads login files like. Hence, you can see that sudo -i simulates an initial root login, including changing the home folder ( $HOME) to root's, rather than your own.

If you run the following commands: $ sudo -i Hence, if you are on a default *buntu install, where root login is disabled, sudo -i can be used while su and its variants cannot. The primary difference between sudo -i and su - is that sudo -i can be executed using a sudoer's password, while su - must be executed with the root account's password. Sudo -i runs a login shell with root privileges, simulating an initial login with root, acting similar to su. Note: This answer has been heavily edited since its last iteration based on Eliah Kagan's comments.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)